+ Adlan Hidayat

If you would like to delve deeper into the dynamics of democratic accountability, I would highly recommend reading the article 'Re-Assessing Elite-Public Gaps in Political Behavior' by Joshua Kertzer. In his research, he finds that political scientists actually tend to overstate and misunderstand the consequences of elite-public gaps in political behavior. In reality, public officials (the 'elites' who make decisions) and the masses (the public) share similar preferences in decision-making. Most of the time, the differences between the public and the masses are actually caused by misperceptions by elites.

Source: Link

+ Sam Slewe

Populism is not the only issue regarding this. We might even ask ourselves what will happen with democracies in the future. In Europe, fewer people are voting, raising the question of whether democracy is still a democracy if turnout rates are declining. As a result of fewer people voting, democratic inequality and prejudice in public policy may emerge. A higher voter turnout rate is required for a functioning democracy. So, this 'trend' also shows a new direction democracy is taking.

+ Chia-Erh Kuo

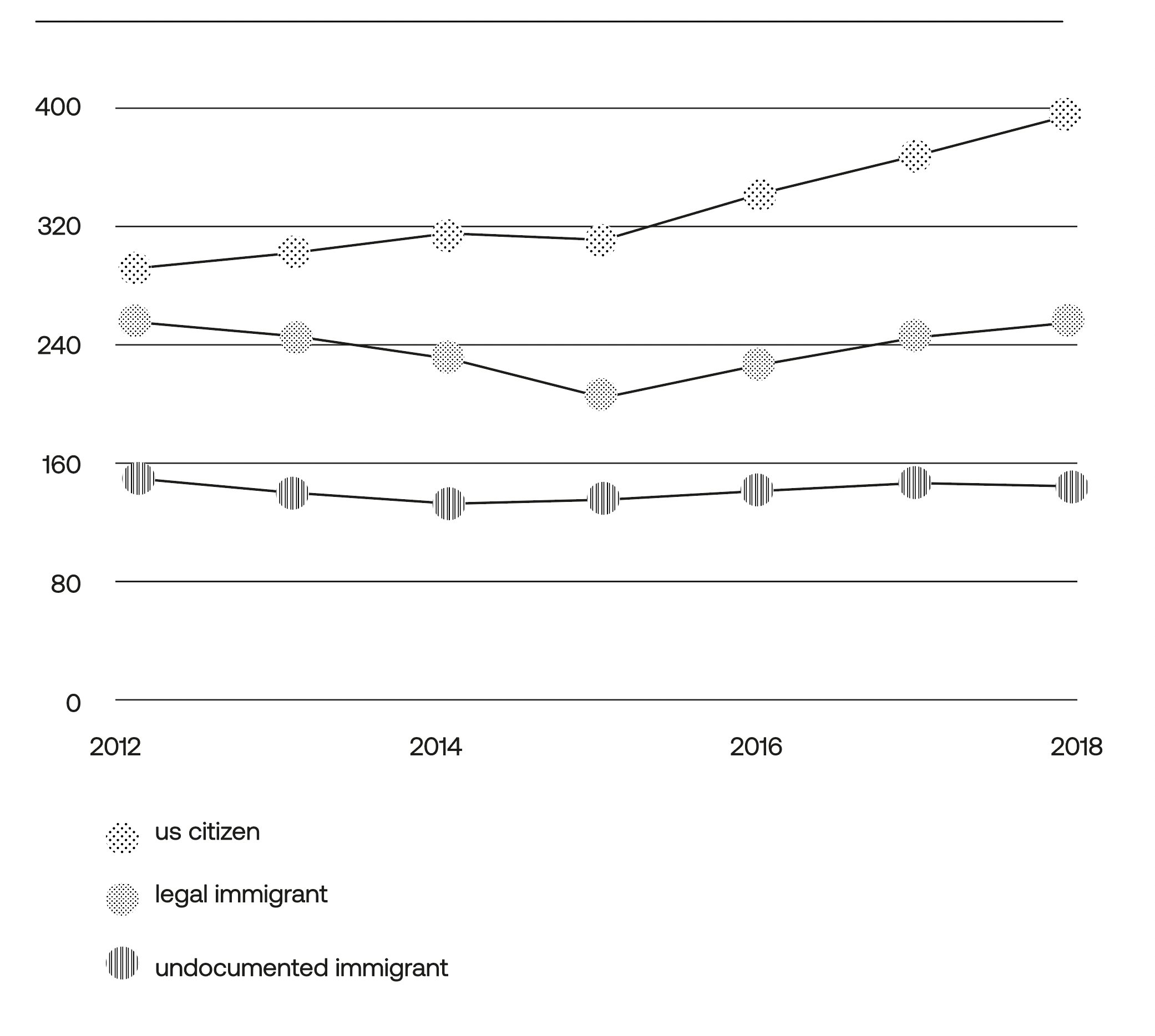

In my opinion, the section answers the four questions very well. And that triggered my curiosity about the negative consequences of xenophobia in people's attitudes towards immigrants and policy advocacy. I recommend reading some case studies about the issue: 'Regionalizing xenophobia? Citizen attitudes to immigration and refugee policy in Southern Africa' by Jonathan Crush Wade Pendleton, 'Xenophobia, asylum seekers, and immigration policies in Germany' by Heribert Adam, 'The political economy of xenophobia and distribution: The case of Denmark' by John Roemer and Karine Van der Straeten.

Source: Link, link, link

+ Daphne Prieckaerts

A few years ago, photographer & world traveler Thijs Heslenfeld invited me to travel to the outskirts of Namibia. After not seeing a human being for two days, we stopped in the middle of the desert to put up our tent and make a campfire for dinner. Then, a furious big black man came towards us out of nowhere on his big bike. He scared the hell out of me. While my instinct told me ‘run,’ Thijs walked towards the man, with open arms and a big smile as if he had known this man since kindergarten, yelling, “what a great bike, my friend.” Instead of running, we talked and drank coffee. The solution to xenophobia might actually be looking into the eyes of the other.

+ Adlan Hidayat

In my opinion, this conclusion leans more towards a pessimistic view. I think that due to the growing prominence of globalization and advancements in technology, society is actually more inclined to accept diversity. This has been evidenced by numerous efforts to support immigration, particularly during times of conflict. In the context of Ukraine and Russia, many have opened their homes to fleeing Ukrainians. After the Trump administration forced migrant children into custody, there was public outcry and efforts to improve migrant rights. Lastly, what the black lives matter movement taught us is that people all over the world believe in the value that everyone should be treated equally.

+ Emma Datema

What, for me, is striking is how over time, those who are understood to be strangers (and thus should be feared) change. In 2016, the Netherlands held a referendum about the Association Agreement between Ukraine and the European Union. It became a major political dispute, with politicians framing it as an issue of national identity and statehood. With a depressingly low turn-out (32.2%), a majority (61.1%) of voters were against closer political and economic relations with Ukraine. Many of these voters ignored arguments that Ukraine should be more closely integrated with Europe out of fear for Russia. Not even 6 years later, there appears to be much unanimity among Dutch society that Ukraine is very much part of Europe. (Rightfully so) Ukrainian refugees are very welcome, with Dutch citizens even willing to drive to the Polish-Ukrainian border to pick people up.

+ Adlan Hidayat

If you like to explore the dynamics between strategic resources and political outcomes, I highly suggest reading 'Carbon Democracy: Political Power in the Age of Oil' by Timothy Mitchell. Throughout the book, Mitchell unravels the link between fossil fuels with the withering of democracy. Conventionally, many assume that the limited forms of democracy in the Middle East are restricted because of cultural and religious practices. In reality, Mitchell argues that the physical properties of oil limit the structure of the political response. For example, Mitchell talks about how the transportations networks of oil eliminate the opportunities for unions and labor rights. Fewer people are required to work, fewer people to supervise, and fewer central hubs. This was all planned to limit communities of workers and to the influences of labor unions, which were prominent with the extraction of coal. As oil companies gained influence politically, a history of pushback was translated institutionally.

Source: Link

+ Elias Sohnle Moreno

There is a theory around this configuration: the resource curse. It would be interesting to see if sand-endowed countries will suffer from its benefit.

+ Adlan Hidayat

If you would like to explore challenges to the institutional framework for development, I recommend reading 'The Problematization of Poverty: The Tale of Three Worlds and Development' by Arturo Escobar. Escobar argues that development professionals (from the UN, World Bank, etc.) sought to devise mechanisms and procedures to make societies fit a pre-existing model. He found that when intergovernmental institutions aimed to help the 'developing world', they didn't aim to understand the particular circumstances, which produced worse outcomes.

Source: link

+ Chia-Erh Kuo

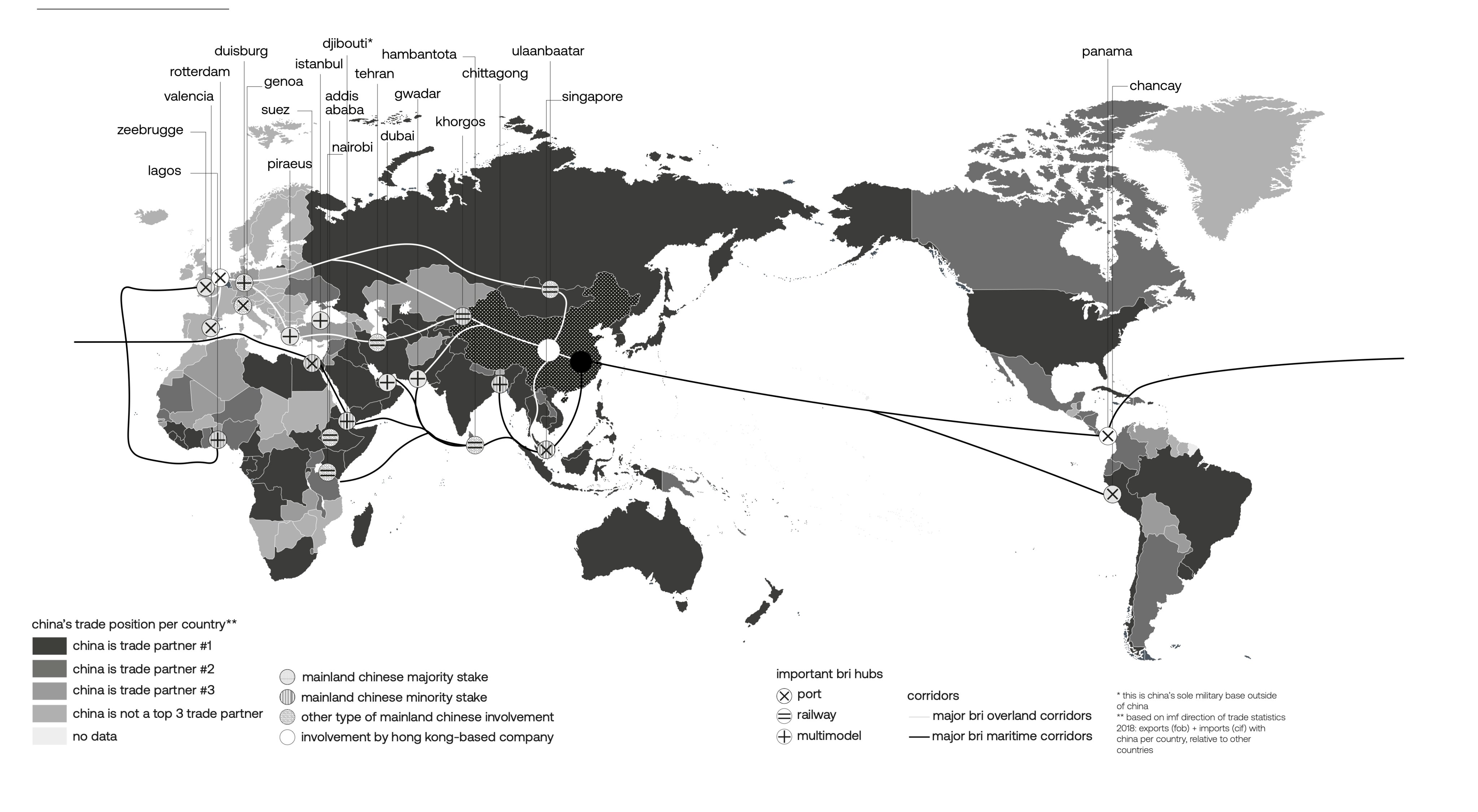

The impact of the China-led initiative is expected to continuously reshape the geopolitical scenarios, given that Beijing has been facing backlash from member countries for years. If you are interested in exploring more about the topic, I recommend reading a recent article about what Russia's invasion of Ukraine could mean for China's BRI.

Source: link, link, link

+ Chia-Erh Kuo

Japan has a similar strategy, intending to balance its interest in regional infrastructure development with suspicions about China. As a result, Tokyo has committed to spending $110 billion on infrastructure projects throughout Asia. In addition, Japan has also agreed with India to develop the Asia-Africa Growth Corridor (AAGC), a project to develop and connect ports from Myanmar to East Africa.

Source: link, link

+ Elias Sohnle Moreno

China is tremendously growing its influence in Sub-Saharan Africa. Sub-Saharan Africa manifests the strongest population growth over the next 50 years, making it the ideal candidate for becoming the new factory of the world. China sees this as a massive opportunity as Chinese labor is becoming more costly and the standard of living increases. China is heavily investing via traditional methods (purchasing land, training workforce, etc.) and loaning almost impossible to repay funds to African public authorities to take advantage of this opportunity. That will often entail strong collateral, creating a potential future dependency on China.

+ Emma Datema

Reaction to the previous comment: Maybe be a bit careful with how strong you make the claims, there is also a lot of criticism that the impossibility to repay the loans is a very western way of analyzing the relationship between China and African countries, and many African countries actually loan much more from western countries/institutions and also private funds

+ Diede Kok

It isn't easy to describe just how historical international cooperation along the Silk Roads truly is. There are historical records dating from 2000 years ago noting the travelers that entered China, what they brought, when they arrived, and when they left; an administration system that is reminiscent of passport control. The Chinese reports refer to the Mediterranean as well as Roman cultures, whose inhabitants were said to be tall and wealthy. The BRI is a continuation of millennia of human history.

Source: The Silk Roads, Peter Frankopan, p. 15-17.

+ Pieter Hemels

It's interesting to see that more and more is being done regarding the accessibility of medicines in low- and middle-income countries. The South African government fought multinational drug companies over access to HIV/AIDS medicines in what was dubbed "Big Pharma vs Nelson Mandela" and won. Since then, the accessibility of medicine has increased significantly. Initiatives like Access to Medicine Index, founded by Wim Leereveld, tremendously impacted big pharma behavior. Organizations like I+ Solutions literally increase the accessibility of medicine by shipping medicines to a billion patients in these areas, financed by UN Global Fund, USAID and others. More and more, these organizations focus on independence for these countries regarding access to medicine.

Source: link, link, link

+ Chadia Mouhdi

I really like how we use the term WANA (West Asia and North Africa) instead of ""The Middle East"". Increasingly, people prefer the term WANA to the Middle East.

The term 'Middle East' was coined over a century ago and is geographically ambiguous. The region is only east when considered from the perspective of Europe. The term WANA is less rooted in political geography but rather in human geography.

Although I am from a country that is often included when The Middle East is mentioned, I only recently learned about the term WANA and why it is preferred to the Middle East. For me, this really made me aware that the western perspective is ingrained in many different facets of life. It makes me wonder what other words and perceptions I take for granted currently. Going forward, I would like to learn more about such sensitivities and be more open minded.

Source: link

+ Martin Bernal Dávila

Have you ever jumped onto a train, downloaded or streamed a film or a piece of music online without paying for it? Have you paid somebody cash in hand, knowing that tax would not be paid on that money? There is an area of freedom that allows people to do wrong things from time to time. Nevertheless, big companies or governments will use all of the future technologies at their disposal to enforce their rules in the future. All these questions and considerations are from Jamie Süsskind's book "Future Politics: Living Together in a World Transformed by Tech."

My questions are more about how democracies and dictatorships will apply these technologies and knowledge; what norms will be reinforced in countries like North Korea, Venezuela, Russia, or the US? How will the concepts of freedom and control be used in politics?

+ Camera Ford

This statement resonates with me because of the slight feeling of hopelessness. Saying that climate change's impact is irreversible feels huge and finite. I've said and thought the same phrase myself, so I understand exactly the feeling. And the projected effects of climate change will indeed be mostly irreversible in our lifetime. But beyond these sobering truths, it also makes me think of Kate O'Neill's book "A future so bright: how strategic optimism and meaningful innovation can restore our humanity and save the world." She says that strategic optimism is the most important element in fighting climate change, building better technology, and addressing society's other issues. The future won't be either a utopia or a dystopia, but it is determined entirely by our actions. So those actions should be guided by a belief that despite the future's risks, we can and will create a future that avoids the worst outcomes.

+ Elias Sohnle Moreno

Post-truth was named word of the year in 2016 by the Oxford Dictionary.

+ Elias Sohnle Moreno

This is a fascinating characteristic of 21st-century society. It has huge sociological implications and shows us how society dictates what is politically correct and what is not and how society enforces social norms in the digital age. It could be interesting to elaborate on the sociological implications for the future.

+ Kim Tan

Such an informational read overall! I think it is also relevant to highlight the importance of business leaders who can execute influence without authority. How can future leaders remain influential in a changing environment without compromising collaboration, focus, reflection, self-assessment, etc.?

+ Chia-Erh Kuo

In my opinion, the rise of the B Corp movement could be seen as a real-life example of purpose-driven leadership. The movement aims to help companies around the world balance profit with purpose, advancing a new model that ensures equity and sustainability.

Source: link link

+ Diede Kok

The global community's challenges seem daunting, but remember an important citation from Franklin D. Roosevelt, a man whose life was riddled with difficulty and strive. His mentality is one of optimism and recalls the essence of the scientific method.

"The country needs and, unless I mistake its temper, the country demands bold, persistent experimentation. It is common sense to take a method and try it: if it fails, admit it frankly and try another. But above all, try something." - Leadership In Turbulent Times, Doris Kearnes Goodwin, p. 181.

+ Sam Slewe

Reading more on political polarization(from a psychological perspective), I recommend reading this book: The Psychology of Political Polarization.

Source: Link