+ Chadia Mouhdi

If you are interested in seeing this with your own eyes take a look here: link

+ Elias Sohnle Moreno

Strange times to be alive.

+ Cato Hemels - Hoff

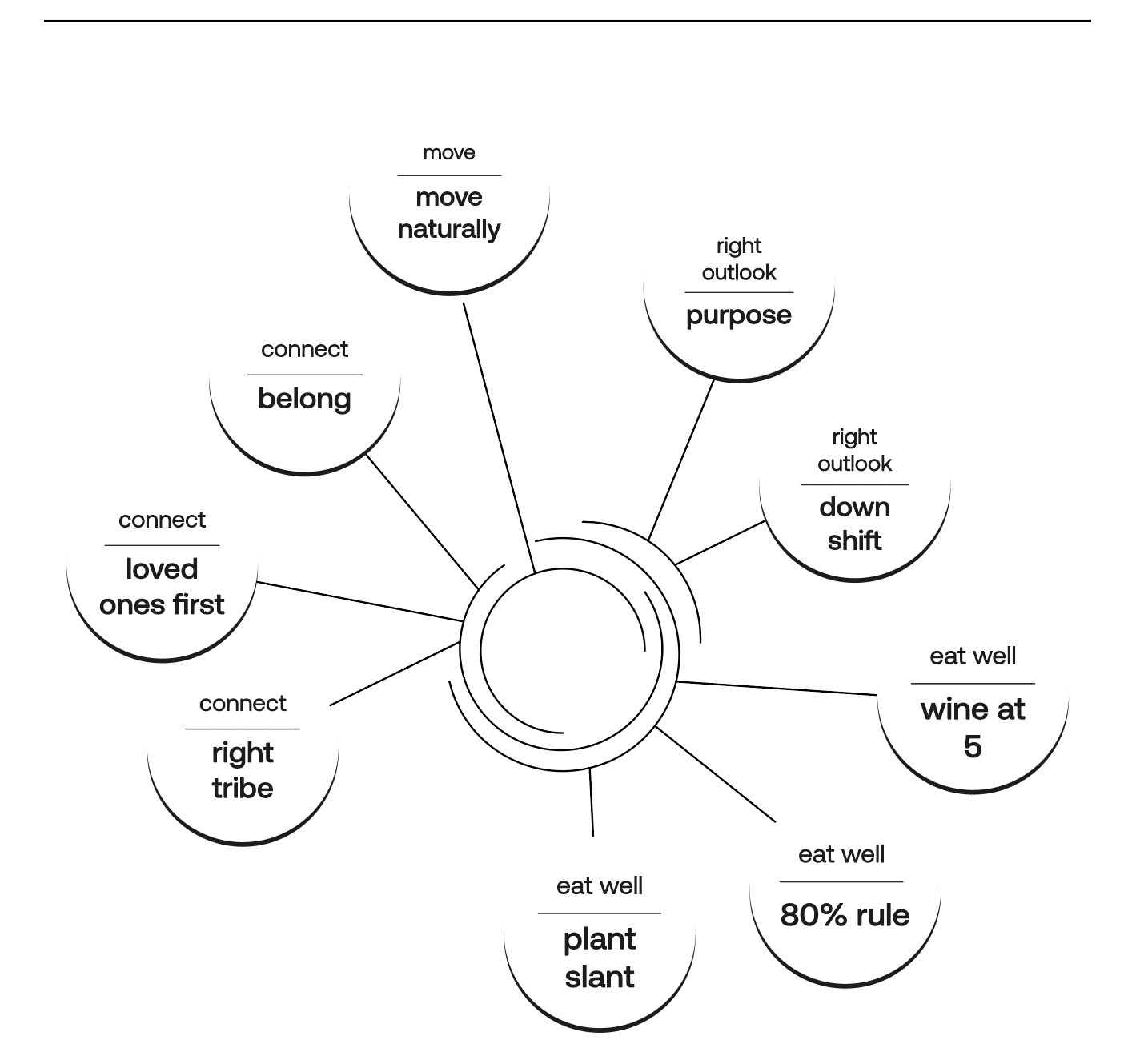

If you are interested in learning more about blue zones and the Power of 9, there is a fascinating, informative website about blue zones: bluezones.com.

+ Diede Kok

Part of this trend is the anti-natalism movement. In 2006, South African philosopher David Benatar's book 'Better no never have been: the harm of coming into existence.' His title may be considered controversial and pessimistic, but the sentiment of 'what kind of world am I bringing a child into?' is growing.

For those who feel inclined to agree with Benatar, I implore you to recognize the growth in wellness, healthcare, and education humanity has reached over the last century. And the decline of violence, war, and crime. I believe that, although there is pain and harm in the world, there is yet more good to experience and contribute to. In the eternal words of Fred Rogers: "Always look for the helpers." Link

+ Stefanie Sewotaroeno

This is exactly what crossed my mind when I started reading this chapter. I have seen the new generation explicitly expressing their wish to not have children on social media. Even married couples are happy with their dogs and do not in the slightest desire to have children.

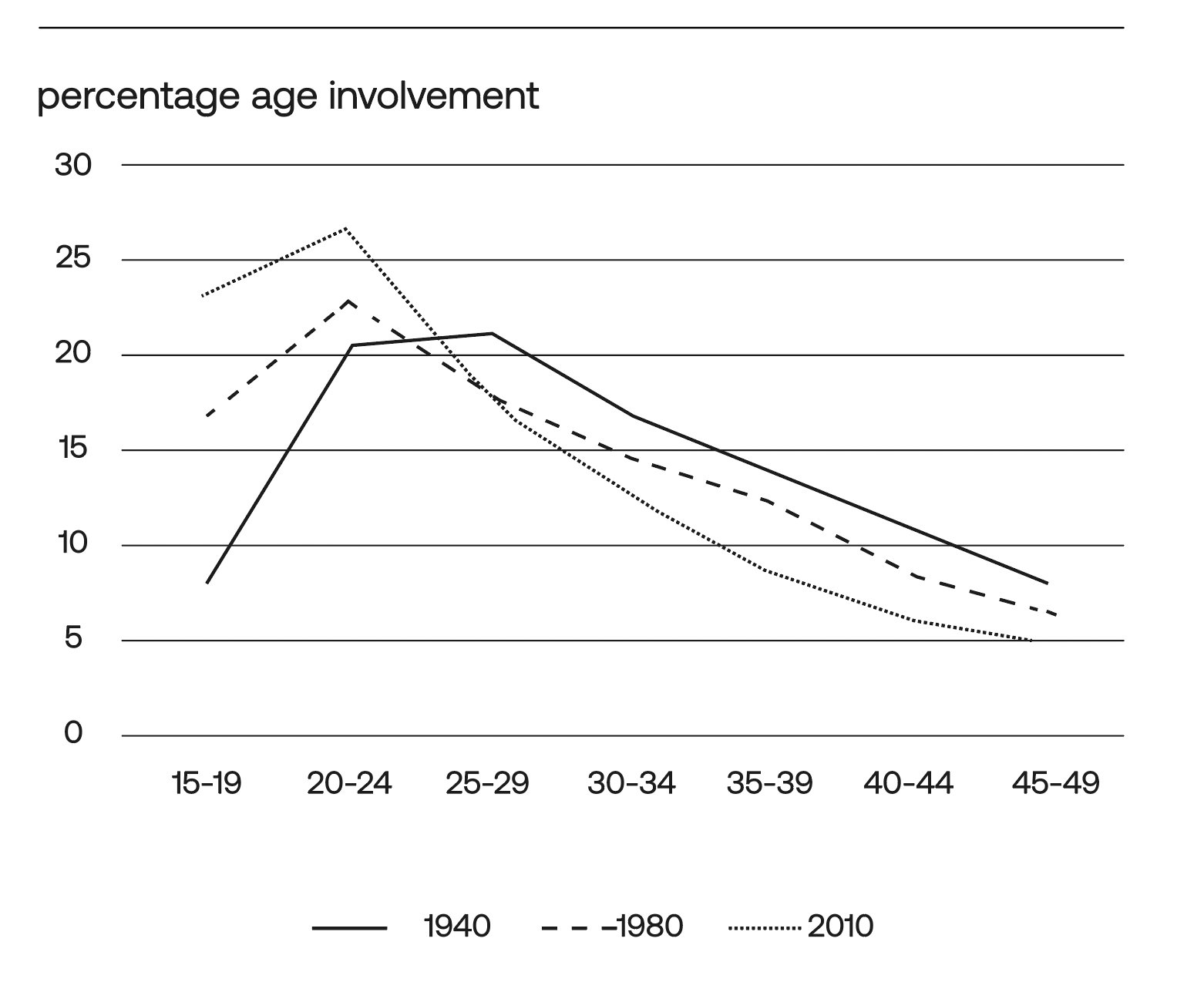

This doesn't seem to be a modern thing, although I do think that modern issues are fueling this. The Washington Post published an interesting article about women having fewer children throughout history:

link.

+ Sam Slewe

Another massive challenge is to investigate the gender pension disparity. In the Netherlands, for example, women receive a pension that is 40% lower than men's. The Netherlands is not the only country that has this gender gap. So, if these demographic factors can be 'handled' in the future of pensions, more has to be done to solve the gender gap.

+ Chia-Erh Kuo

Apart from rising demand and low-interest rates, there is also a cultural aspect behind the soaring housing prices. In Asia, people are more likely to desire to own a property as an asset, whilst western people may only want a house as a place to live. And this long-lasting mindset, to some extent, has led to speculations in the booming real estate market, making housing unaffordable for the younger generation in South Korea and Taiwan. In addition, some have warned that a global housing-market bubble could happen in the near future.

Sources: link, link, link.

+ Diede Kok

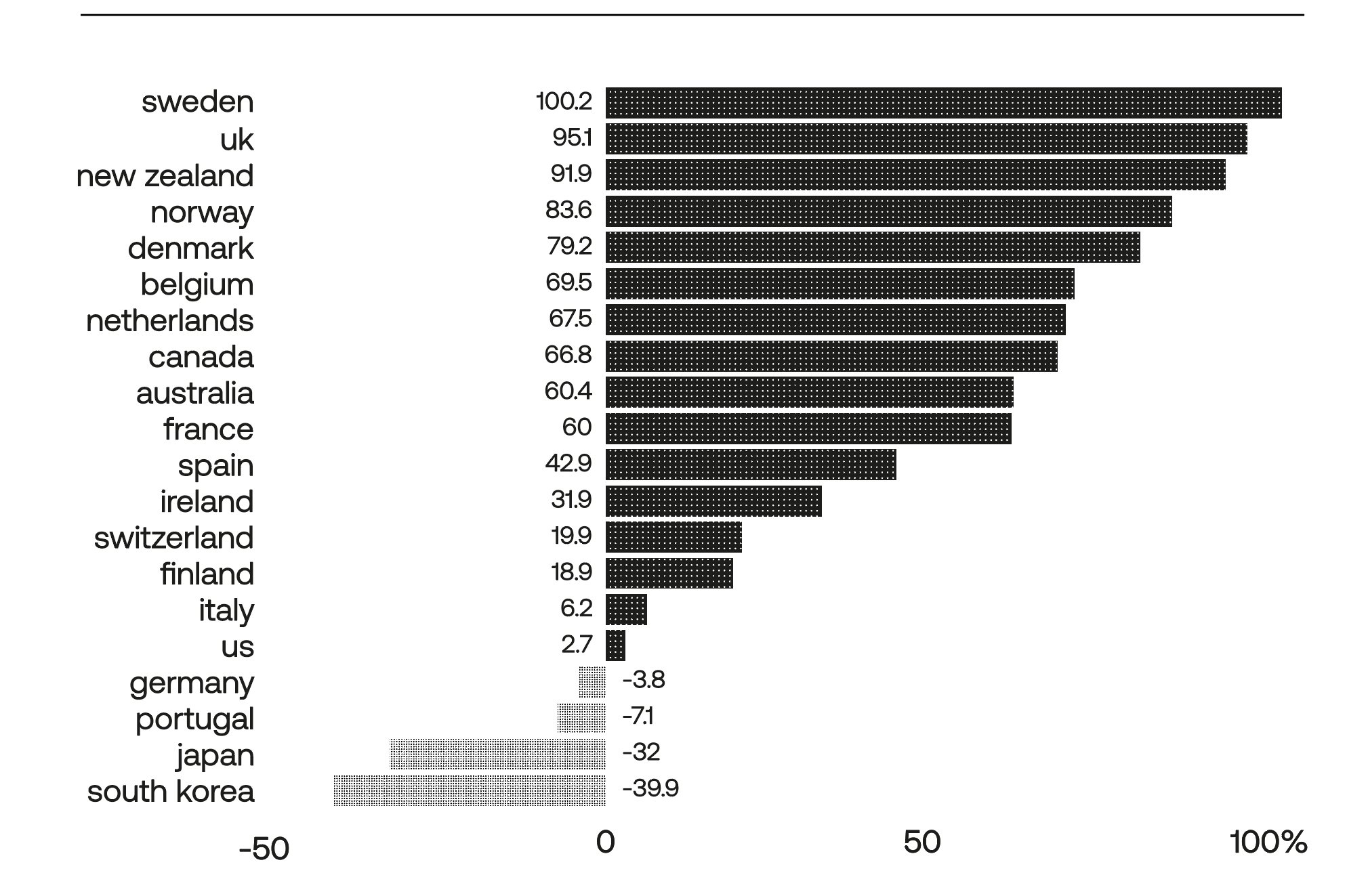

The Canadian solution! Whereas near all countries of the world will face declining populations, Canada is one of the only countries to keep growing. The reason? Canada has historically been much more tolerant towards migration. An average of 300.000 people move to Canada every year from all over the world. That number is estimated to rise to over 450.000.

What does this mean? This means that Canada will be able to afford healthcare, public pensions, and stem the rise of the retirement age. Do these people fall into poverty and crime, as some stereotypes make us believe? Emphatically not, as proven by the data.

Canada is already dubbed 'the most cosmopolitan country in the world'. Issues that will plague the rest of the world in 2100 might be avoided by Canada. Let's be like the Canadians.

Source: 'Empty Planet', Darrel Bricker and John Ibbitson, p. 207-208.

+ Martin Bernal Dávila

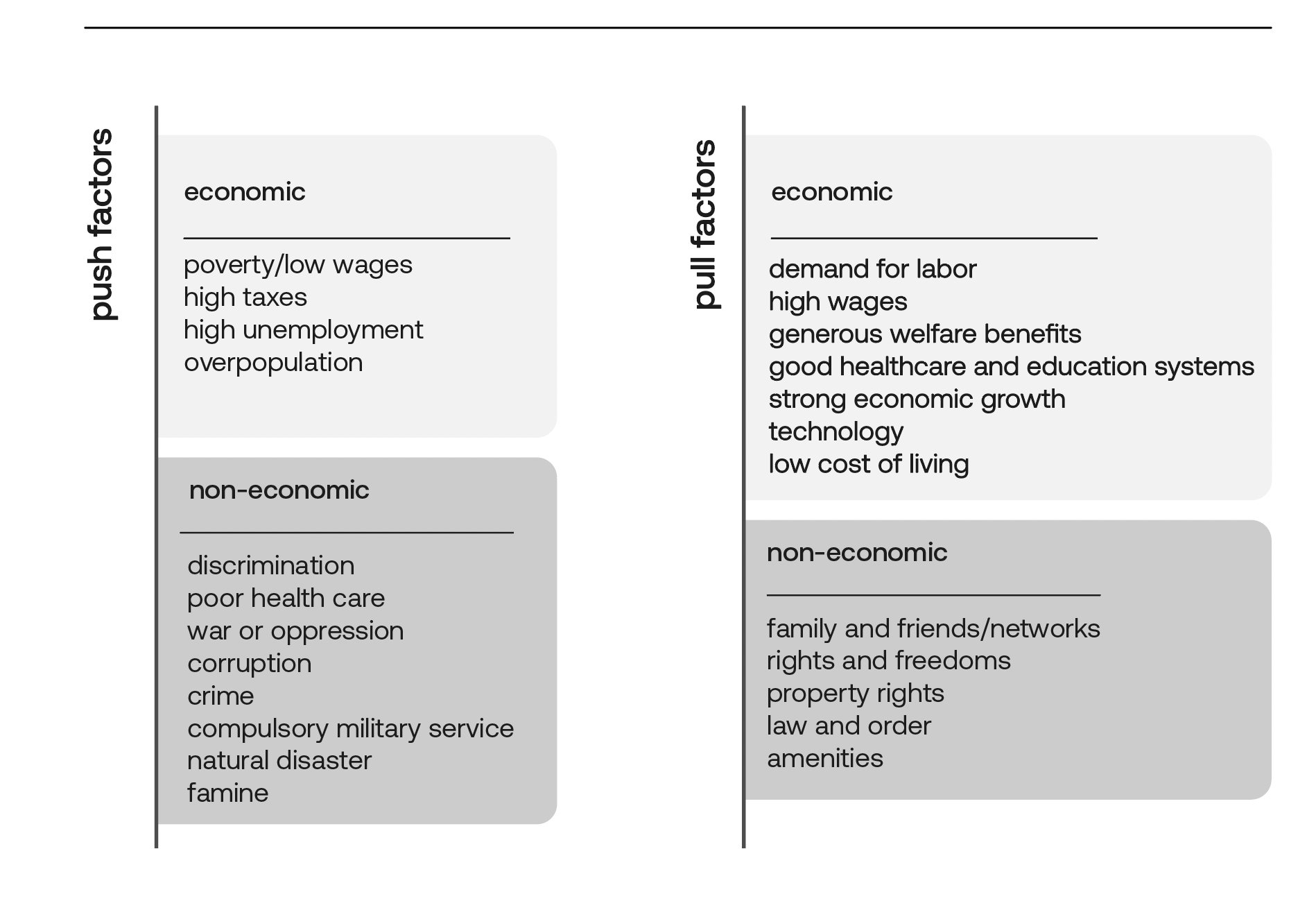

In the case of Ukraine, people have the opportunity to migrate because of their passports. On other continents, humans do not have the same chance or rights. In the future, hopefully, people will be able to migrate if their lives are at risk. Let's see humans, not nationalities.

+ Diede Kok

The writer of the book 'factfulness', Hans Rosling, wrote about the human 'blame instinct'. Rosling concluded that to overcome the human blame instinct (i.e., our tendency to seek a person to blame when faced with adversity) can be overcome by 'looking for causes, not villains'.

When we look for causes instead of villains, we are more likely to look in the mirror, and ask ourselves 'what is my part in this?'. When migrants drowned in the Mediterranean Sea in 2015, the outcry of the general public pointed to human traffickers as the cause of this misery. But European immigration laws are also a cause for migrants to enter frail boats to cross the sea. Let's look for causes, not for villains.

Source: Factfulness, Hans Rosling, p. 214.

+ Stefanie Sewotaroeno

Interesting food for thought to consider is the future evolution of humans. What is next for humanity? Is there a "next" at all? Some say that humans will develop higher consciousness. Others state that we have come to the end of human evolution.

An interesting read is this study by Jeff Morgan Stibel that says that our brain size is decreasing. Quoted from the pdf: "While more work is needed, the overall results of the various GWAS studies that have examined evolutionary changes to cognitive ability suggest that both general cognitive function and educational attainment are under negative selection pressure. While the genetic correlations and underlying relationships are still not fully understood, the data support a genetic decrease in cognitive ability consistent with an evolutionary decline in brain size." link

+ Elias Sohnle Moreno

The taboo around death in Western societies strongly influences our fear of aging. The shared tacit denial of our own vulnerability and mortality makes us react negatively to the exposure to the inescapable prospect that is common to all humans: death. It could be interesting to investigate whether societies that cultivate less taboo around death also experience less fear of aging and ageism.